More Ways to Die from Opioid Prescription

By Liz Savage, Guest Blogger Cathryn wrote a great piece for the NewYorker.com last December about the controversial new painkiller Zohydro, which was approved by the FDA despite the agency’s own advisory panel’s recommendation against it. Since then, Zohydro has remained in the headlines, as vocal opponents of the drug have publicized its potential for abuse -- and more broadly, the role it has played in our nation’s current public health crisis. However, an equally potent painkiller, Moxduo, which is under FDA review, appears to have slipped beneath the media’s radar.

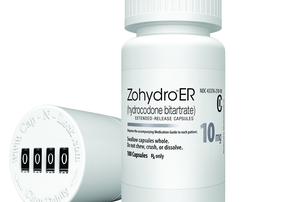

Zohydro is an extended-release, long-acting painkiller -- an “opioid analgesic” -- made from hydrocodone, a controlled substance that can be highly addictive. (Until now, hydrocodone was available in combination with acetaminophen, in such drugs as Vicodin.) Zohydro’s FDA labeling approved the painkiller for round-the-clock use in chronic non-cancer pain patients, a group that includes back pain patients. There are no evidence-based studies to show that high-dose long-term opioid treatment is an effective therapy for such chronic pain patients. Even in patients who take the drug according to prescription, physical dependence will occur, requiring increasingly high doses. Tapering is difficult, and may be impossible. In addition, Zohydro is manufactured in a form that readily allows recreational users to crush it into a powder that can be snorted or injected to get an immediate high.

The response to Zohydro’s approval was swift. Attorneys general from 28 states (and Guam) wrote to the FDA requesting a reversal of the drug’s approval. Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., and Rep. Stephen Lynch, D-Mass., have also introduced legislation to rescind the FDA’s approval of Zohydro.

Manchin’s bill comes after he and Senator David Vitter, R-La., investigated allegations that faculty members at the University of Rochester and the University of Washington arranged meetings between pharmaceutical industry members and FDA officials in exchange for payment of $25,000 to $35,000 per meeting. “We are also troubled by the role the pay-to-play meetings may have played in the recent approval of Zohydro ER, a controversial new prescription painkiller,” the senators wrote in a letter to the dean of the University of Rochester’s medical school.

But the most notable opposition to Zohydro came from the governor of Massachusetts, Deval Patrick, who enacted a first-of-its-kind ban of the drug in late March. “We have an epidemic of opiate abuse in Massachusetts, so we will treat it like the public health crisis it is,” said Gov. Patrick.

The ban singled out Zohydro, prohibiting doctors from prescribing it and pharmacies from selling it. “Until it is available in an abuse-deterrent form, or better, until the Secretary of HHS or the Congress has acted on the requests to overturn the FDA, Zohydro will not be available in Massachusetts,” Patrick said.

In what may be the first such effort in pharmaceutical history, Zogenix, the maker of Zohydro, filed a lawsuit to overturn the ban, and the district court judge sided with the drug company, saying Massachusetts could not override the federal approval of a medication. “It would undermine the FDA’s ability to make drugs available to promote and protect the public health,” Judge RyaZobel wrote in her ruling. She added that a state could not compel Zogenix to replace Zohydro with an abuse-deterrent version because the new form would first need FDA approval. (Zogenix announced Friday that the company will sell its migraine therapy business to provide the capital to focus on developing of an abuse-deterrent form of Zohydro.)

“Although the ban may prevent someone from misusing the drug, the ban prevents all in need of its special attributes from receiving the pain relief Zohydro ER offers,” Zobel wrote, a comment that suggests unfamiliarity with the range of pharmaceuticals available to treat pain, as well as other options for pain treatment.

In response, Patrick authorized statewide restrictions on Zohydro. Doctors who wish to prescribe the drug must now complete a risk assessment on the patient and a “pain management treatment agreement” that requires drug screening and monitoring of the number of pills prescribed. The doctor would also have to take part in a prescription-monitoring program that tracks how often he or she has prescribed Zohydro.

Vermont has similar restrictions in place. Patients there must sign an informed consent form that details the dangers of the drug. In addition, doctors must declare that no alternative medications are available for that patient, but such a declaration would be inaccurate, since the market is overrun with options. Doctors risk losing their licenses if they don’t follow the new rules.

Many doctors won’t need such restrictions to keep them from prescribing Zohydro. Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire confirmed that its doctors won’tprescribe Zohydro.

Physician advocacy groups like Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing have been active in the push to rescind FDA approval. The group’s president, Andrew Kolodny, MD, an addiction psychiatrist, told CNN, “It's a whopping dose of hydrocodone packed in an easy-to-crush capsule. It will kill people as soon as it’s released.”

The FDA’s commissioner, Margaret Hamburg, MD, spoke last week at the Rx Prescription Drug Abuse Summit in Atlanta and addressed many of the public’s and medical community’s concerns about Zohydro. She stood by the FDA’s approval of the drug, describing the agency’s decision as a balance between the concerns over opioid abuse and the needs of patients in pain. “Stemming the rise in opioid misuse, abuse, addiction and overdose is a huge challenge, but one that we are deeply committed to addressing along with our federal partners and so many other partners and stakeholders,” she said. “But we also must meet the very real medical needs of the estimated 100 million Americans living with severe chronic pain or coping with pain at the end of life, which is also a major public health problem in this country.” Her commentary implied, inaccurately, that there were no other suitable opioid analgesics already on the market.

She also said that Zohydro is not unique in its potency—something that has been a major source of concern among Zohydro opponents. It is the nature of extended-release opioids to have more of the active drug in each pill than in shorter-acting forms like Vicodin, she said. That statement was accurate, but omitted the explanation that in fact, there is no evidence for the efficacy of high-dose, extended-release opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain, and therefore, no reason to prescribe such drugs.

Meanwhile, as previously noted, the newest opioid painkiller, known as Moxduo, is moving swiftly through the FDA approval process. Moxduo combines morphine and oxycodone into what Kolodny calls the “perfect product” for addicts. “It’s offering nothing new, and because it’s more dangerous than the competing product, we think it will exacerbate the opioid addiction epidemic,” the psychiatrist said.

Many were encouraged when the FDA’s advisory committee voted 14-0 against Moxduo’s approval. But since a similar panel also voted against Zohydro, and the FDA gave the manufacturer the go-ahead anyway, there is reason to think the FDA may once again ignore the committee’s recommendation. If this happens, it may be that the FDA and painkiller manufacturers are indeed in cahoots, determined to bring these drugs to market at any human cost, as Manchin and Vitter have claimed.

The FDA’s approval of Zohydro (and potentially, Moxduo) may be setting a dangerous precedent that will allow drug companies to develop new opioids that will exacerbate the addiction problem that already plagues most regions of the U.S. And there’s yet another drug making its way through the FDA’s approval process

Several days ago, Purdue Pharma filed a New Drug Application with the FDA for a once-a-day hydrocodone bitartrate pill. The Purdue drug would compete directly with Zohydro, but it also includes an abuse-deterrent that makes it slightly harder to crush or snort. (Studies have shown that the abuse-deterrent property is not particularly effective; the Web is full of instructions on how to get around it).

It appears that Zohydro, which is produced by a small pharmaceutical company, may have been set up as the FDA’s sacrificial lamb. Given Purdue Pharma’s irresponsible track record with OxyContin, a drug that spurred the largest pharmaceutical public health crisis in history, it is likely that public health officials would instantly rebel at the prospect of another high-dose long-acting opioid from the same manufacturer. Zohydro’s approval sets a precedent, however, making it impossible for the FDA to deny approval of a substantially equivalent drug, such as the one that Purdue has proposed.

As the maker of OxyContin, Purdue is not known for its safety record. The release of OxyContin launched the prescription drug abuse epidemic. In 2011, physicians wrote just under 250 million prescriptions for opioid analgesics, for about 100 million patients. That’s almost double the number of prescriptions that were written for these drugs in 2001. According to the Center for Disease Control, doctors ordered enough prescription painkillers in 2010 to medicate every American adult around the clock for an entire month. The opioid business is now worth about $8.5 billion a year to drug companies. In 2012, 16 million Americans, aged 12 and older, reported having ever used oxycodone products nonmedically, and two percent of eighth graders and 3.6 percent of high school seniors have abused OxyContin in just the last year.

Not surprisingly, this pharmaceutical bonanza has been lethal. The unprecedented rise in overdose deaths in the U.S. parallels a 300% increase since 1999 in the sale of these strong painkillers. According to the CDC, these drugs were involved in 14,800 overdose deaths in 2008, more than cocaine and heroin combined.

These statistics are a grim reminder of the addictive clout of these painkillers, and forecast what we can expect -- an exponential increase in the numbers of overdose deaths and destroyed lives -- if additional (and entirely unnecessary) opioid analgesics win FDA approval.